The Imagination of our Hearts

These words are not easy to comprehend. I was challenged. About a year ago, I went back to the church where I served for over 20 years, up in Newton. It was good to see those people again. It was particularly nice to see the children whom I had baptized coming up for the children’s message. But I found myself with the challenge of trying to explain such words as these, such a notion as this, that we would eat and drink the body and blood of Jesus. I actually had the hubris – the arrogance – to think that I would have a way of doing that, of making this text and words like it seem reasonable and not “yucky,” nor an endorsement of cannibalism. But these dear children humbled me. They pushed back and they said “Really? Nah. No.” They were honest: it made no sense to them.

We all need those moments of humiliation to put us in our place. But the challenge of thinking how it is that we can, and do, believe this — or maybe don’t, but just kind of let the mystery be — that remains with me.

It seems striking to me that this passage, these words from Jesus which speak in this crude, shocking way about his body, his flesh, his blood, and eating and drinking, how it is that they occur in this Gospel of John. For many people the Gospel of John is the the most spiritual and spiritualizing of the Gospels. It is one in which there seems to be, and has been, in the usage of the church, a dualism between the flesh and the spirit; between the body and the soul.

The Gospel of John is indeed profoundly dualistic, which is one of the problems that it has. It has been used sometimes to encourage the most harmful aspects of our tradition: that kind of demeaning of the flesh; that kind of contempt for the body; that kind of insistence that all that matters is the soul, all that matters is the spirit, all that matters is the spiritual meaning of things. The Gospel of John could easily be read that way.

And yet, as I think about this today, it is in the Gospel of John that we have another way of speaking about the flesh. That the “Word becomes flesh,” and that Jesus speaks of his flesh as that presence now, that dwelling with us now. And here we are joined to that flesh in this very fleshly way. This carnal way. This incarnation into real flesh, and our dependence upon that, so that we might be joined to that flesh. Take it into ourselves as we take food and drink. To be joined to the body of Christ, to the flesh of Christ. To be joined to this flesh together, so that we are all of us of one body. We all share one blood — we are blood family, across all the races of the world. Across all the divisions of the world. Those for whom he came and died, those for whom he gave himself. We are joined in this intimate way as we eat and drink.

This is powerful, intimate, language. And it is language which we have not been willing to give up, and say “oh we’re only talking symbolically. We’re only speaking of a metaphor.” Well of course it’s symbolic! Of course it’s a metaphor. But we would speak it with the specificity and the physicality of our experience. That we taste it. That we are reminded, again and again, that we have taken it into ourselves. That it is joined to the very tissues of our physical existence.

There’s been a a lot of emphasis in modern reflection, and in scientific theory, about whether we are simply physical. Whether our thoughts are simply electrochemical in the brain. Whether there really is a distinction between the mind and the brain. But it seems to me that we need not be threatened by that thought, if in fact we are Orthodox Christians who believe in the incarnation. That there’s even a kind of materialism in our faith that says faith that says “yes, I am this flesh. I am this body. I am this. But what that means is that I am joined to the Flesh of Christ.” I am joined, body and soul, mind and brain, and I can taste it in my mouth. I take it into myself. “We are what we eat,” as we are reminded. And we are of Christ.

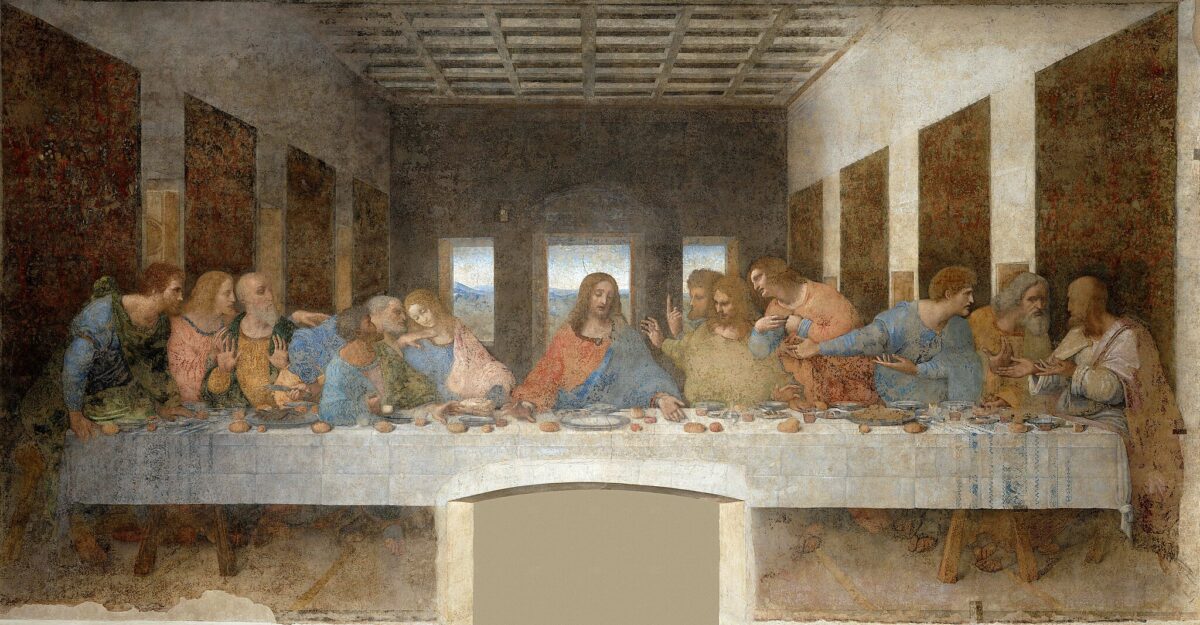

If I may reflect for a moment about the different ways in which Christians have talked about our communion, our eating and drinking together. It seems to me that you can think of it as a kind of a continuum, depending on where you stand. An anthropologist might say “oh, what these Christians are doing, is that they have come together to remember – in an act of remembrance. ‘For the remembrance of me,’ as he said.” We are enacting a memorial meal so that we might remember this foundational story of how he gave himself, and how he spoke at that last gathering with his disciples before his passion. It is a memorial. We can understand that anthropologically. So there’s a part of the reformed tradition, the so-called Zwinglians, who said “yes, don’t complicate this. Just understand that it’s a memorial meal. That’s what it is.”

In the reformed tradition, John Calvin was a little different. He said “Yes, of course it’s a memorial. Of course it’s a meal of remembrance. Of course that’s why we eat and drink. But, you see, this is a work of the Spirit. The Holy Spirit is present and at work in our remembering. It is a gift of Grace.” And then of course we have those who say “Oh, but for us, when we experience that, when we do that, when the holy spirit moves us, then the bread and the wine become the body and blood. It really happens for us. Indeed, it happening is not dependent upon us. The real presence of Christ, which then happens, is something that does not depend on our perceiving or our believing. It is really there. That’s how we think of it. That’s how we lay ahold of it, if we do lay ahold of it. And even if we don’t lay ahold of it, it is still there extended to us. It is still real. Christ really comes. Christ really appears.”

And then we Lutherans, we actually take that a little further, and we say “yes, it is not dependent upon us. Jesus says he will be there and he is. It’s not about some magical mystical change in the bread and the wine. It’s simply that, as he said, he is really present, truly present.” Those are the words of faith. Those are the words of the imagination of our hearts, as we stand, or kneel, or sit and receive this food and drink. That’s a good biblical phrase, “the imagination of our hearts.” It is our imagining, but when we imagine, though, we might say “it has not happened yet,” or “this is a metaphor,” or any of that. But in the imagining, we lay hold of it and it shapes us. It shapes the way in which we understand ourselves and one another; the way in which we know our God.

I’m reminded of something that the Danish theologian and philosopher Søren Kierkegaard wrote. He said “people think that being in the church is like going to the theater. Here you are in the audience, and up there is the preacher. It’s like the theater, where you have the player and the audience.” But he said (in Danish) “Det er skør!” That’s crazy – it’s not like that at all. For, you see, you are the players. it is happening to you as you worship; as you listen. It is happening in your heart; in your mind. That’s where the action is. You are the player; God is the audience. And then he said, “Well, what about the preacher? What about the choir? What are they?” And he said “hviskenderne.” They’re the whisperers, which is what they called the prompters. They tell you the words. They give you the words, but the thinking and the feeling and the imagination of your hearts, that is what God is watching. You are the players, in your hearts, in your imagination. Let it shape you. And when you come, let this taste, let this promise, let this sign of Christ’s presence shape you.

I’ll say one little thing more, because it has so struck me, these last several weeks as I’ve worshiped, that in the liturgy that we’ve been using in most of our churches around here, and and also here this morning, there’s so much talk about abundance. So much talk about “there is enough.” There is plenty. We had it at the beginning: it’s hard to believe that there’s enough to share, but there is. In our confession it speaks of the abundant love, the abundant work. There is always more than enough. Christ has set the table with more than enough for all. Come. And in the end of the service we pray, “Jesus, bread of life, we have received from your table more than we could ever ask.” There is abundance. Jesus said “I came to bring them life that they might have life.” Life abundantly… plenty.

But we live in a world where, of course, there’s scarcity. Are we in denial about that? Are we in denial about climate change? Are we in denial about what may happen with our resources? Are we merely spendthrift? No. We need wisdom. Our texts also speak of wisdom about that.

But this language of abundance is so fundamental in our faith, in the face of even great scarcity, to continue to know abundance. To know the abundance that we have. To be grateful, to be people of gratitude and people of generosity. To be bold enough to let our imaginations be shaped by the language of God’s abundant love.

Our liturgies have been imposing that language upon us. Does that work? Does forcing you to speak about abundance actually make you more grateful? Actually make you more generous? I don’t know. But I do know that if we take this to heart… I do know that if we let our imaginations be shaped: by grace, by gratitude, by a sense of abundance, by a crazy faith that we have life — life beyond even this life. That, as Jesus says, though we die, yet we will not die. That that’s not our destiny, that our meaning is greater than that. To let our imaginations so be shaped, will be to be more like those people in other parts of the world who live, not with grasping, not with the fear of losing, not with clenched fists, but with open hands.

I hear again and again from people who have been to the poorest parts of the world, and they say “I couldn’t believe how generous people were. How hospitable they were. How they had so little, but they were willing to share.” What kind of courage? What kind of trust? What kind of imagination of the heart might it be that works such wonder? How was it that people gathered around Jesus shared, and those five little loaves and those two fish were enough to feed the multitude? How could they believe that?

May the imagination of our hearts so be shaped by what we eat, by what we drink, by what we remember, and by what our God has seen in us, his beloved children.

Amen