You are the witnesses of these things

In this first letter of John, somebody is writing to a Christian community that is restless. They don’t know exactly what they’re supposed to be doing. It’s now been a generation or two, maybe three, since the events of Luke’s gospel, and these early Christians are finding themselves questioning what this is all about. To become a Christian, after all, meant stepping out of your old social circles and it may have even meant being ostracized by your family. It meant adopting a different set of social values, one that didn’t make a distinction between Jew of Greek, slave or free, male or female, as Paul wrote to the Galatians. It meant rejecting the strict social hierarchies of their world—which always meant throwing your lot in with those at the bottom of those hierarchies. And here we are, the community is saying, having sacrificed what we ‘ve sacrificed, and… for what exactly? Jesus doesn’t seem to be coming back. We don’t seem any different. The world doesn’t seem any different. What’s the point, anyway?

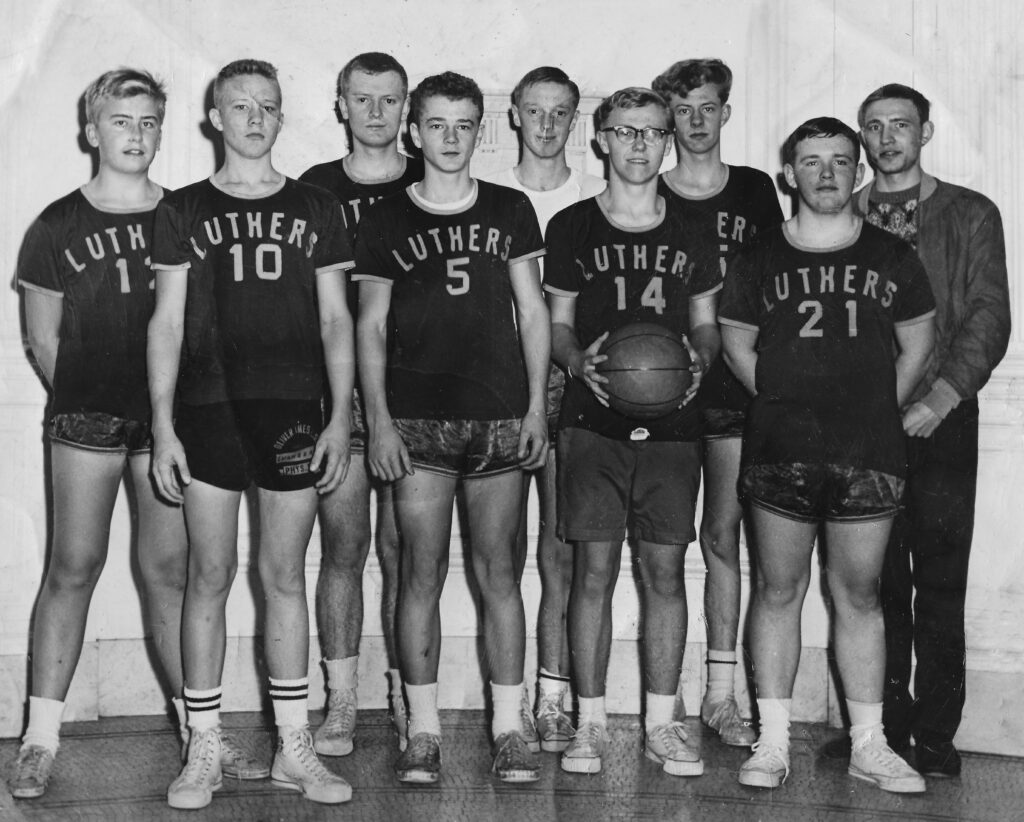

And here we are, all these many generations later, perhaps wondering some of the same things. The community in John is a few decades removed from the resurrection and the excitement and energy of a new beginning, and we gathered here are a few decades removed from full churches, Lutheran bowling leagues perhaps, new members being received on a regular basis. Not that long ago, the Church was at the center of our society, but we can’t be that anymore. Whatever passed for “Christian ethics” and morality, passed for everybody’s ethics and morality. And now the world has changed.

For some, Christianity, or any religion, just doesn’t provide any meaning. For many of us, Christian “ethics and morality” turned out not to be as ethical or moral as we thought, even as we ourselves have adapted and changed we are just starting to glimpse the damage that’s been done. And for others, it’s simply easier to get out of the habit, as we watch our children and our friends change their minds, choose to stay home or go hiking on a Sunday morning, content to leave Christian communities behind.

Like that community in 1 John, we may be left asking just what our purpose is here. Twenty centuries removed from that Upper Room, the world doesn’t seem any different. We don’t seem any different. What difference does any of this make anyway? We are restless and estranged and wondering just where it is we’re supposed to be going, just what it is we’re supposed to be doing.

“Don’t you see,” John writes to his friends. “Don’t you see, that we are God’s children?” We are God’s children now, not in some far off future that we are sitting around and waiting for—now. That is what is so remarkable for the disciples standing in that Upper Room. They are there, hiding, afraid that they will be on the next cross, afraid that they’ve been duped into following a fake Messiah, afraid that the rumors they’ve been hearing about the empty tomb are bad news—afraid—and the Jesus comes and stands among them: Peace be with you. It wasn’t into some other world, some far off future world, that Jesus was resurrected; it was into our world. Into the world of flesh and blood and human fear and frailty.

“You, frightened ones, You, confused and unsure ones, You are God’s children, now,” he tells them. “And this is the love that God has for you.”

In all our fears and worries and uncertainties, in all the ways we can feel overwhelmed by the world, in all the ways the world can make us feel like we don’t belong and become tempted to make others feel like they don’t belong—into all of us, the risen Jesus comes and stands among and with us: Peace be with you.

And that word that was spoken in the Upper Room so many centuries ago is spoken to each of us, in waters of our baptisms and in the bread and wine of this meal: “Peace be with you. You are a child of God, and nothing you ever do and nothing that is ever done to you can ever take that away.”

Standing in the midst of our fears and worries, standing in the midst of the challenges surrounding us, Christ speaks this word to us—Peace be with you—so that we can speak this word to others.

And so just as centuries ago, in the community John was writing, too, we step out of the norms and morals of the society around us. to embrace the life-changing love that we have seen. When our world tells us that we are to amass power to control others, to rise above and put others beneath us, we instead embrace the power of loving others. Our call is not to be at the center of our society, but to work to make Christ’s love the center of our world. Our call is not grow our numbers as if we were trying to win a popularity contest, but to grow our faith so that we can stand amid the hurting and lonely, inviting them into these healing waters.

And when we see others using our Christian faith to shame and marginalize others because of who they are or who they love, we will instead we recognize that the God of love has made us to love one another and has made humankind beautiful and variable across many spectrums. And so we work for a world where love is valued for love, where all people can feel safe being themselves.

And when those around us embrace cruelty and contempt, and try to make themselves feel bigger by making others feel smaller, we will stand with all of God’s children, showing solidarity with those who are hurt and remembering that so many hurt others out of their own fear, remembering that we are all in need of God’s graceful forgiveness.

Because God comes and stands among us and declares us beloved, we go into the world to live among God’s other beloved children, working to make new life in this world, in this world of the resurrection. That is the difference the love of God makes to us and for us.

And that is who we are as the Church. We are the people who have been in the Upper Room, who have heard the words of the Risen Christ: Peace be with you. And we are the people who go into the world to love as we have been loved.

Amen